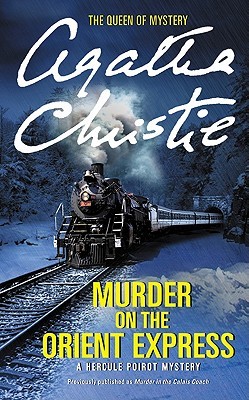

Murder on the Orient Express is the

first Agatha Christie book that I have read. In fact, it is the first

murder-mystery that I have every read, so this was a new experience for me on

many levels. I would say that it was a pleasant experience. Christie’s writing

is clear and concise. She is not heavily descriptive but does not contrive

moments when important clues are offered to the reader. It is an easy but fun

read with a good twist in the end. It is the conclusion of the work that has

left me thinking.

Spoiler Alert! This whole

reflection is based on the conclusion of Christie’s book. So if you don’t want

to know whodunit, then you probably should not continue reading. Seriously,

stop reading. I may not say what happened, but I don’t want to be held

responsible for ruining your fun and exciting read. So here comes the spoiler:

After reading Christie’s work I am

left with the question, “when is it ok for a group of people to take justice in

their own hands?” In this work a man commits a horrible crime and because of

his connections with the mob and the money he has he is not convicted. The man

is allowed to go free even though everyone knows he is guilty. Not only has

this man murdered a kidnapped child, the characters in the book argue that he

is responsible for the death of the child’s parents and one other person. Thus

the man has the deaths of a multitude of people on his hands and he does not go

to prison; he is not punished. To many in the book such an injustice cannot go

unheeded and a group of people connected with the crime and family involved

decide to take matters in their own hand. This man ends up murdered by twelve

(or thirteen?) other people.

When is it ok for a group of people

to take the law, or justice in their own hands? Were their actions just? Did

they do the right thing? I hope this is not an easy question to answer.

First, we have a system of laws to keep society from resorting to a mob

mentality. As a rule, the whim of the mob is seldom the best thing. Think

of the scene in To Kill a Mockingbird

when Atticus Finch is in front of the jail doing all that he can to keep a mob

of men from lynching the innocent (although presumed guilty) Tom Robinson. The

mob is seldom right (except in the random Simpsons

episode) and the law is supposed to protect the individual from mob rule. Yet

when that system of laws breaks and does not see that justice is served what

then? The legal system is far from perfect. It can be manipulated. It can be

misused. It can cause an innocent man to suffer and allow the guilty to go

free. When this happens the purpose of the law falls away, people are not

protected, and it is easy to see why some might feel that the best recourse

would be to take matters into their own hands.

Second, consider the notion of justice. There are many different

approaches and understandings to the concept of justice from MacIntyre to Rawls

to Aristotle and many more. Justice could be a working towards equilibrium, a

fair distribution of goods, or a punishment that is comparable to the crime.

Justice could be relational and communal or abstract. However justice is

understood, it is important to remember that the legal system is not always

just and laws do not always serve the cause of justice. That is why our

lawmakers have the power to change them. The system is constantly being fixed

(and broken and fixed and broken). So in the case of The Orient Express one could argue that justice was not served,

that an injustice was allowed to continue, and it was imperative that the group

of people did whatever they could to make things right.

Third, consider the punishment of death. Is it just to take someone

else’s life? I imagine that many, considering the man murdered a child and was

responsible for the death of others, would say that it is right to take his

life. They would argue that the crime is so severe that the only recourse would

be to kill the man. What does that achieve? In his work Discipline and Punishment, Foucault considers the idea of the

purpose and goal of punishment as a deterrent and corrective for the convicted.

Taking a life may serve as a deterrent but offers no corrective, no option for

penance and/or reform for the convict. Is the individual so far gone that his

or her life no longer has any value? Leaving such a question up to a small

group of people (not an impartial jury by any means) is dangerous at best.

If I were

to take issue with Christie’s work it is that this moral dilemma seems to be

addressed very lightly. Hercule Poirot, the great thinker, does not give the matter

deep thought, does not wrestle with what might be the “right” thing to do. What

is important is that he solves the mystery. This gives short change to an

important question that drives the motive and much of the book. Here is where I

would encourage you to watch the movie.

There are a number of television/film

adaptations of this book. The 2010 version (AgathaChristie’s Poirot version that was on A and E) is one that shows the Poirot

struggling with the ethical dilemma. Poirot is torn because he understands the

danger of allowing a group of people take the law into his own hands. Yet he

also understands the dilemma they faced and why they made the decision to

murder a man who seemed to have sense of morality at all. This movie adaptation

shows the pain and the worry and the anguish that Poirot wrestles with in

deciding to not implicate the group of people.

What is right? What is just?

Christie’s book asks such questions but does not delve into them. I guess that

is the difference between a fun mystery and a good novel.

No comments:

Post a Comment