A review/reflection of Stephen Puleo's book Dark Tide

What is 15 feet high,

travels at 35 miles an hour, and is sweet and sticky?

If you guessed “lollipop rocket ship” than you are wrong and

need to get your head checked. But if you guessed molasses on January 15, 1919

in Boston’s North End then you are correct. Give yourself a star.

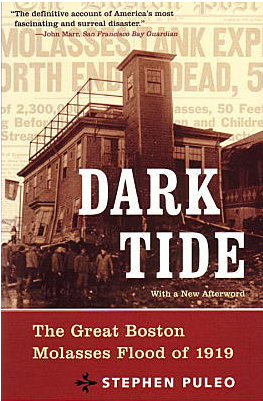

Stephen Puleo’s book Dark

Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919 is the only definitive work

on this tragedy, and it is good. Puleo spends time investigating not only the

events themselves as well as the aftermath, but the threads of the American

experience that are connected to this bizarre disaster. For example he spends

time considering the story of the anarchist movements in America in the early

20th century as well as the experience of Italian-Americans in that

time period (there was considerable overlap between the two). It is a good

historical work that not only tells the story of Boston’s North End, but of an

aspect of the American experience

Now for another question:

What has no height

but looms large, never moves but is always just beyond reach, and is dark and foreboding?

If you again guessed “lollipop rocket ship” then you

seriously need to get your head checked. Really, there is something wrong with

you. But if you guessed scapegoats

then either you are really, really intuitive and smart, or you read ahead and

cheated. No star for you!

Scapegoats are those persons, things, ideas that we used to

cast blame, to hold up as responsible, and to assuage ourselves of any guilt.

While Puleo does not mentions the notion of scapegoats in his work, the idea

holds a strong narrative thread. As labor conditions worsen and workers rights

have yet to be articulated in the early 20th century, anarchists

were one of those groups that rose to give voice to the frustration and despair

that many workers in America were feeling. It is true that many also gathered

with communists, with socialists, and with other leftist dissenters. Many

represented immigrant communities which had little or no voice in the political

system or with the powers that be. Many were involved with worker’s strikes,

protests, and rallies. And sadly, many were involved in violent activities

damaging property, wounding and sometimes killing people. Puleo sets the

backdrop of the anarchist movement in the early 20th century without

taking away from the main story including the trails of Sacco and Vanzetti.

They are not portrayed as great people, but are not portrayed as the cause of

all that is wrong with all that is wrong in the world. Yet that is what happens

in the trail that takes place after the accident in 1919. In the trail the

company that was responsible for the giant molasses tank make a fervent

argument that it was an anarchist who placed a bomb in the tank causing the

destruction and the death. The anarchists become the scapegoat.

Such an argument is not surprising as it is something that

we continue to see today. If something goes wrong we look to the group that we

have been taught to distrust and blame them first. Terrorists, gang members,

kids, ants, Republicans, Democrats, ranting preachers, and others all get on

the list of people that we like to blame and use as the focus of our ire. The

problem is that when we do this we are often allowing ourselves to be

distracted from some of the deeper, more complex nature of the problem. We can

be lulled into a false story that a company built a great molasses tank that

was a symbol of the strength of American Industry but then some evil and nefarious

men who didn’t want to see America succeed snuck in a blew up the tank not

caring about the loss of innocent life. Or we can look at the story that Puleo

offers that tells about the lack of a political voice in the Italian community,

the nature of the North End of Boston, the lax regulation and oversight from

the government, and how a drive for profit can lead people to cut many corners

at what turned out to be a great expense.

We continue to create scapegoats today. We say that public

schools are so bad because the kids are bad or the parents are bad or the drugs

are bad but do not speak to the inequitable funding via property tax or the

history of redlining and highway creation destroyed many neighborhoods and thus

their schools. We say that one political party or another is the cause of all

that is wrong in the world but do not speak to the ways in which companies fund

both parties in such a way as to keep the common interest out of the political

process. Even in churches we say that it is the music or the preaching that is

the cause for people staying or leaving but do not speak to the ways in which

the general approach to church and faith has become a secondary (or lower)

aspect of peoples lives… including those who still claim to believe.

Scapegoats are easy. Scapegoats are quick. Puleo shows the

depth that each problem offers and the richness that can be found in a

thoughtful investigation.

Down with Scapegoats!

Those jerks.

No comments:

Post a Comment